Prologue: A City on Edge

In the final hours of 1884, as Austin, Texas, slept, a new kind of terror crept into its bedrooms. The victim was Mollie Smith, a 25-year-old African American domestic servant. Attacked with an axe as she slept, she was dragged into a backyard and brutally mutilated. This was not a crime of passion or a simple robbery; it was the opening act of a year-long nightmare. The killer, whom writer O. Henry would later dub the “Servant Girl Annihilator,” launched a series of attacks that would claim eight lives, injure at least six others, and plunge a burgeoning capital city into paranoia. Operating three years before London’s Jack the Ripper, this phantom with an axe presented America with one of its first documented serial killer crises, a case steeped in the racial and social complexities of the Reconstruction-era South.

The Killer in the Shadows

NAME: Unknown

ALIAS: The Servant Girl Annihilator; The Austin Axe Murderer; The Midnight Assassin

NO. OF VICTIMS: 8 killed, 6-9 attempted, 2 assaulted

SPAN OF CRIMES: December 30, 1884 – December 24, 1885

STATUS: Deceased (presumed)

A Year of Blood: Case History

The Annihilator’s campaign followed a grim, escalating pattern. After Mollie Smith in December 1884, 1885 unfolded as a horrifying calendar of violence. In May, Eliza Shelley and Irene Cross were murdered. In August, an 11-year-old girl, Mary Ramey, was killed, and her mother, Rebecca, was severely wounded. In September, Gracie Vance and her boyfriend, Orange Washington, were bludgeoned to death. The spree culminated on Christmas Eve, 1885, with the simultaneous killings of two white women: Susan Hancock and 17-year-old Eula Phillips. This shift to white, middle-class victims sent seismic waves of panic through the entire city, transcending the racial divides that had initially framed the public perception of the crimes.

The chaos at the crime scenes—bloody axes left behind, victims dragged from their beds—initially suggested a gang or multiple culprits to authorities and a terrified public. The police force, overwhelmed and under-resourced, made hundreds of arrests, including the husbands of the final two victims. James Phillips and Moses Hancock were tried amid public fury, but convictions were unstable and ultimately overturned, leaving the true perpetrator at large.

Modus Operandi: A Chilling Signature

The killer operated with a specific, brutal ritual. Victims were almost exclusively attacked at night, indoors, while asleep. Many were then dragged outside, where the final, sexualized violence occurred. Beyond the bludgeoning and stabbing, the Annihilator left a macabre “signature”: the insertion of sharp objects into the ears of at least six victims. This act, with no tactical value, was a psychological compulsion, a “calling card” that linked the crimes to a single, disturbed individual—a concept modern criminology understands well, but which baffled 19th-century investigators.

Profile: Constructing a Phantom

Modern analysis, notably by former FBI profiler Mark Safarik and geographic profiler Kim Rossmo for PBS’s History Detectives, sketches a likely portrait:

* GENDER: Male

* PATHOLOGY: Serial Killer; Serial Rapist; Hebephile/Ephebophile (evidenced by victim age range)

* SIGNATURE: Insertion of objects into victims’ ears; removal of victims to outdoors.

* PROFILE: A young, physically strong male, likely in his early 20s. He was probably a “disorganized, anger-retaliatory” offender, attacking women as surrogates for deep-seated personal rage and humiliation. He likely felt powerless in his daily life, possibly in a servile position himself. Geographic profiling suggests he knew Austin’s alleyways and yards intimately, likely working in or around the commercial hub of Congress Avenue. His initial focus on African American servant girls—women with limited societal power—suggests a preference for accessible targets, with his confidence growing until he crossed the era’s stark racial line to attack white women.

Known Victims: A Tragic Roll Call

The Annihilator’s victims were predominantly young African American women navigating a precarious existence in post-Civil War Austin:

* Mollie Smith (25, killed Dec. 30, 1884)

* Eliza Shelley (30, killed May 6, 1885)

* Irene Cross (33, killed May 22, 1885)

* Mary Ramey (11, killed Aug. 30, 1885)

* Gracie Vance (20) & Orange Washington (25, killed Sept. 28, 1885)

* Susan Hancock (41) & Eula Phillips (17, killed Dec. 24, 1885)

Their stories are a grim lens into the vulnerabilities of Black women’s lives in the 19th-century South, where their deaths initially drew less urgent attention from power structures.

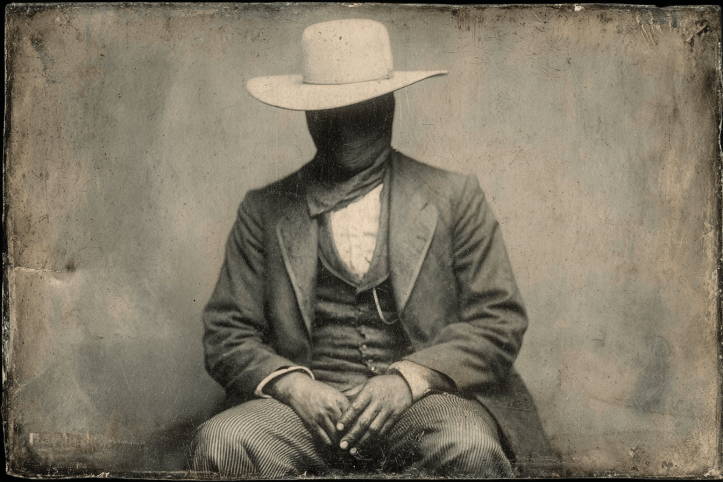

The Search for a Face: Eyewitnesses and Suspects

Eyewitness accounts were chaotic and contradictory, reflecting the panic of the times. The killer was described as white, Black, “yellow” (light-skinned), a man in a dress, or a man with a face covering. Some reports claimed an accomplice. This fog of misinformation highlighted the investigation’s desperation.

While many were arrested, one name has emerged from history as a compelling suspect through modern re-investigation.

Nathan Elgin: The Prime Suspect

In February 1886, just weeks after the Christmas Eve murders, Austin police officer John Bracken shot and killed a 19-year-old African American cook named Nathan Elgin. Elgin was in a violent frenzy, assaulting a woman named Julia with a knife. The autopsy revealed a critical detail: Elgin was missing a toe on his right foot.

This was the “smoking gun” authorities had secretly held. At multiple crime scenes, particularly in the soft soil of yards where victims were dragged, investigators had found distinct bare footprints with a missing toe. They had never released this detail to the public. In Elgin, they had a dead man who physically matched the unique evidence.

Nathan Elgin – A Criminological Analysis

Elgin fits the Disorganized/Anger-Retaliatory (D/AR) serial killer profile with striking alignment:

* Childhood & Motivations: Born in 1866, Elgin worked as a “servant” from a young age—a position of subservience that could foster deep resentment. Historical records hint at a violent temperament; in 1882, he sent a “reckless and bloodthirsty” letter threatening a deputy sheriff. This fits the profile of an individual who externalizes his internal rage onto authority figures and, ultimately, onto surrogates who represent his humiliation.

* Locational Expertise: Elgin grew up in Austin’s Wheatville Freedman’s community, adjacent to the crime scenes. His known movements placed him at the center of the killer’s geographic profile.

* Escalation & Signature: The progression from non-fatal assaults on sleeping women in mid-1884 to the overkill, sexualized axe murders mirrors classic escalation. The specific ritual—attacking a sleeping woman indoors, then moving her outside—matches Elgin’s alleged final, frenzied attempt to drag his victim from a saloon to a private yard.

* The Cessation: The murders stopped abruptly after Elgin’s death. While not definitive proof, it is a powerful circumstantial closing of the loop.

Defense attorneys for the wrongly accused husbands later used the Elgin connection in court, with Sheriff Malcolm Hornsby testifying about the footprint match. The city, desperate for calm and perhaps reluctant to admit a single Black man had evaded its entire establishment, never officially closed the case with Elgin as the culprit.

Conclusion: An Unquiet Grave in History

The Servant Girl Annihilator case is more than a prequel to Jack the Ripper. It is a stark tableau of Gilded Age America—its racial fractures, its evolving urban anxieties, and its complete lack of framework for understanding predatory, psychosexual violence. The initial muted response to the murders of Black servant girls, followed by city-wide panic when white women were killed, speaks volumes about the era’s hierarchy of victimhood.

While Nathan Elgin remains the strongest candidate based on physical evidence, locational logic, and behavioral profiling, the case is officially cold. The Annihilator’s true name is buried with his victims, a permanent shadow on Austin’s history. His legacy is a grim milestone: a blueprint for the modern serial killer, written in blood on the Texas frontier before the world even had a name for such a monster.

Sugden, P. (1994). The Complete History of Jack the Ripper. Carroll & Graf.

History Detectives. (2014, July 15). Austin Axe Murders [Season 11, Episode 5]. PBS.

Texas Monthly. (2000, July). Capital Murder.

Ressler, R. K., & Shachtman, T. (1992). Whoever Fights Monsters. St. Martin’s Press.

Vronsky, P. (2004). Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters. Berkley Books.