The Face in the Lantern: An Introduction to an Enduring Haunting

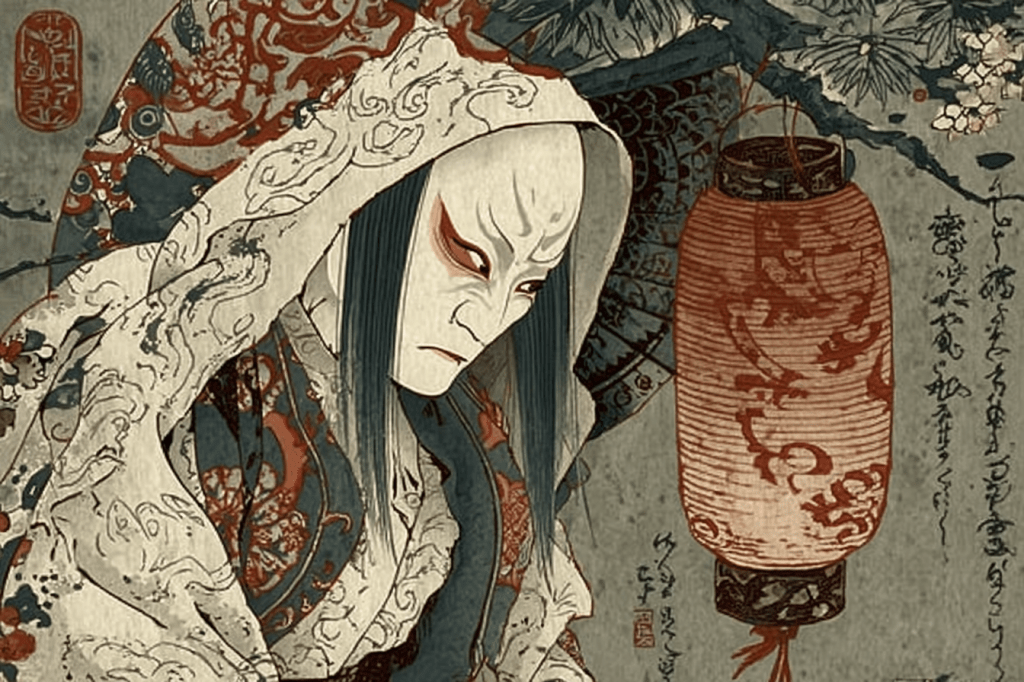

In the flickering glow of a paper lantern, a face materializes. It is the face of a woman, beautiful yet grotesque, with one eye drooping in a grimace of eternal agony and fury. This is not a face you forget. It is the face of Oiwa, the vengeful spirit at the heart of Yotsuya Kaidan, Japan’s most famous and frequently told ghost story. For nearly two centuries, the tale of her betrayal and the curse that followed has seeped into the very marrow of Japanese horror, evolving from a scandalous Kabuki play into the foundational myth of Japanese horror itself. This is more than a ghost story; it is a cultural artifact, a lens into the anxieties of the Edo period, and a blueprint for the vengeful spirit that continues to haunt modern horror.

This blog post will dissect the anatomy of this undying legend. We will journey back to 1825, to the raucous theater where the ghost of Oiwa first stalked the boards, and follow her spectral path through two centuries of woodblock prints, silent films, and J-horror classics. We will explore the five-act tragedy of the original Kabuki play, examine the real-world scandals that gave it life, and trace the ghost’s unrelenting journey into modern pop culture. This is the story of the curse that refuses to die.

A Ghost is Born: The Kabuki Stage and the Social Chills of Edo

The year is 1825. In the bustling, pleasure-seeking city of Edo (modern Tokyo), the theater is the nexus of popular culture. Playwright Tsuruya Nanboku IV, a master of the macabre, is under pressure. His task: create a companion piece for the season’s main event, a production of the classic samurai revenge epic, Chushingura. What he delivered was not a side-show, but a seismic shock to the Kabuki world.

Yotsuya Kaidan was a sensation precisely because it was so different. It broke from the high-flung world of noble samurai and epic battles. Instead, it was a kizewamono—a “raw-life drama” that dragged the grimy, desperate lives of common people into the spotlight. Its central monster wasn’t a demon, but a human monster: the weak, greedy, and treacherous ronin, Iemon. The play was a double-feature, performed on alternating days with the noble Chushingura. Audiences would watch the 47 loyal ronin avenge their master one day, and the next, witness a lowly ronin murder, betray, and be driven mad by the very social order the samurai code was meant to uphold. It was a subversive, scandalous, and utterly compelling mirror held up to the era’s anxieties.

The Anatomy of a Ghost: The Five Acts of a Tragedy

The original Kabuki play unfolds in five distinct acts, a structure that methodically builds from human cruelty to supernatural vengeance. This structure is crucial to its power.

Act 1: The Seeds of Betrayal. We are introduced to Iemon, a disgraced, poverty-stricken ronin, and his gentle wife, Oiwa. When Oiwa’s father, Samon, confronts Iemon about his inability to provide, a fit of rage leads Iemon to murder him. This initial act of violence is not just a murder; it’s the first crack in the moral and social order that will eventually swallow Iemon whole. The act establishes the grimy, desperate world of the play.

Act 2: The Poison and the Pledge. The plot thickens with the introduction of Oume, a wealthy woman obsessed with Iemon. To clear his path to a more advantageous marriage, Iemon conspires with Oume’s family. They send Oiwa a poisoned “beauty cream.” The ensuing disfigurement is a scene of legendary horror in Kabuki. As Oiwa applies the cream, her face begins to blister and contort. When she looks in a mirror and sees her own ruin, her mind begins to shatter. In a final, tragic accident, she falls upon Iemon’s sword. With her dying breath, she doesn’t weep; she curses. This moment of betrayal, disfigurement, and death is the crucible in which the ghost is forged.

Act 3: The Haunting Begins. The ghost of Oiwa makes her first, iconic appearance on Iemon’s wedding night. As he lifts his new bride’s veil, he does not see Oume’s face, but the grotesque, disfigured visage of Oiwa staring back. This is the legendary chochin-obake (lantern ghost) scene, where Oiwa’s face appears in a paper lantern, a moment of theatrical and psychological horror. This act is not a passive haunting. Oiwa’s ghost actively manipulates Iemon, driving him to murder his new bride and her family in a blind, Oiwa-induced rage. The ghost is not a specter to be feared; she is a weapon of divine, terrible justice.

Act 4 & 5: The Curse Unfolds and the Unraveling. The final acts are a masterclass in psychological and supernatural unraveling. The subplot involving Oiwa’s sister, Osode, and the villainous Naosuke, concludes in a tragic twist of incest and suicide. Meanwhile, Iemon, now covered in innocent blood, is completely isolated. The ghost of Oiwa is no longer merely a spectral presence; she is an inescapable presence. She is in the sound of rain, in the flow of the river, in the face of every stranger. Iemon, pursued by her curse, descends into absolute madness. He is no longer a villain to be feared but a pitiful, broken man, haunted to the point of psychological obliteration. The play concludes not with a heroic showdown, but with the total annihilation of Iemon’s world, a fate arguably worse than a simple death.

The Historical Echo: The Real Horrors Behind the Ghost

The genius of Tsuruya Nanboku IV was his ability to weave the play’s roots in the soil of Edo’s own scandals. Yotsuya Kaidan is a ghost story with a real-world heartbeat. Nanboku is believed to have drawn from two infamous, real-life crimes that shocked Edo:

1. A case where two servants murdered their masters.

2. The horrific story of a samurai who, discovering his wife’s infidelity, bound her and her lover to a wooden door and threw them into the Kanda River to drown.

By weaving these true-crime elements into the story of Iemon and Oiwa, Nanboku blurred the line between sensational fiction and the terrifying reality of the city’s underbelly. The horror was not in some distant, haunted castle, but in the tenement next door. The ghost story was a mirror, reflecting the anxieties of a rigid social order where women and the lower classes were powerless. Oiwa’s transformation from a victimized wife into the all-powerful onryō was a fantasy of agency and retribution for the powerless.

The Anatomy of an Onryō: Why Oiwa Haunts Our Imagination

Oiwa is the archetype of the onryō (vengeful spirit), and her design is a visual code. Her white burial kimono (shiroshōzoku) marks her as one of the dead. The stark white makeup (oshiroi) on her face is the pallor of the grave. Her long, unkempt hair, often shown as patchy from the poison, is a classic yūrei (ghost) trope. But Oiwa has her own unique, terrifying signature: the drooping, disfigured eye, a direct result of the poison, and a symbol of her victimhood and the injustice done to her.

This specific iconography has become the DNA of Japanese horror. The pale, long-haired ghost with obscured features (like Sadako in Ringu) is a direct descendant of Oiwa. She is the original “vengeful spirit seeking grudge,” and her influence is the bedrock upon which modern J-horror is built.

The Unkillable Story: From Woodblocks to Silver Screens

The story’s power lies in its mutability. It has been a constant in Japanese popular culture for 200 years.

* Ukiyo-e (Woodblock Prints): Artists like Utagawa Kuniyoshi and Yoshitoshi created stunning, dramatic prints of Oiwa and Iemon, spreading the story to those who couldn’t attend the theater.

* The Silent Screen: Yotsuya Kaidan was adapted for film as early as 1912, and the silent era saw numerous versions. The visual language of cinema was perfect for the story’s ghosts.

* The Golden Age of Kaidan Eiga: The 1950s-60s were a golden age. Nobuo Nakagawa’s 1959 Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan is a Technicolor masterpiece of Gothic horror, while Kenji Misumi’s 1965 version is a stark, psychological nightmare. Shiro Toyoda’s Illusion of Blood (1965) brought a lavish, psychological intensity to the tale.

* Modern Echoes: The influence is everywhere. In The Ring (1998), Sadako’s emergence from the well is a direct visual and thematic echo of Oiwa’s curse. The vengeful ghosts of Ju-on: The Grudge are spiritual heirs to Oiwa’s relentless wrath.

A Legacy in Two Graves: The Living Curse of Oiwa

Perhaps the most potent testament to this story’s power is the superstition that surrounds it. In Japan, it’s said to be cursed. Productions are rumored to be plagued by accidents and bad luck. To this day, it is considered proper—almost mandatory—for actors and directors to visit the gravesite of the real woman who (according to legend) inspired Oiwa, to ask her spirit for permission and protection before a production. This blurring of fiction and reality, of actor and ghost, is the ultimate testament to the story’s power.

Conclusion

The ghost of Oiwa is more than a specter in a play. She is a cultural icon, a vessel for centuries of social anxiety, artistic expression, and primal fear. From the wooden planks of the Kabuki stage to the flickering light of a cursed videotape, her story of betrayal, poison, and relentless vengeance continues to haunt because it speaks to a fundamental fear: that the injustices of this world will not be forgotten and that the oppressed may yet have the final, chilling word. Yotsuya Kaidan is not just a ghost story—it is Japan’s ghost story, and its haunting is far from over.

* Reider, N. T. (2001). Transformation of the Oni. Asian Folklore Studies.

* Shirane, H. (Ed.). (2002). Early Modern Japanese Literature. Columbia University Press.